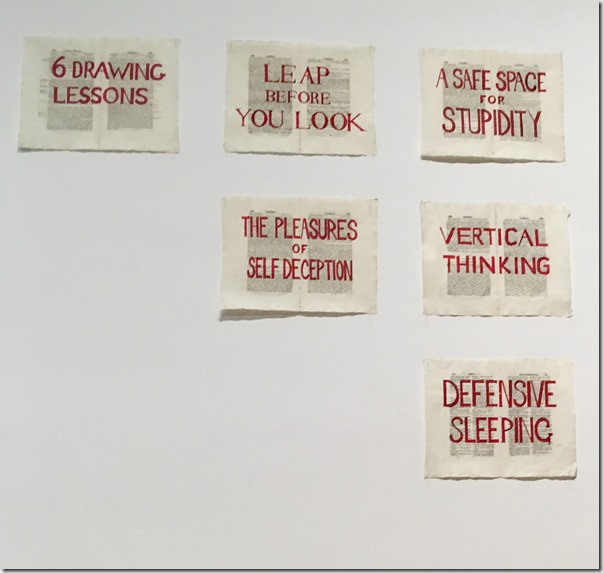

‘Thick Time’ is the title of William Kentridge’s exhibition that has just closed at the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester; and to which I returned, for a second visit, a few days ago. The exhibition guide quotes Kentridge as saying that he is interested in ‘political art’, a term that the quote instantly qualifies “… that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings”. I’m not sure that would be most people’s instant definition of ‘political’ but it has all the more significant ring to it for that very reason. ‘Six Drawing Lessons’ was the title given to a series of (six) lectures Kentridge delivered at Harvard in 2012 but, as this partial image (above) of a wall at the Whitworth suggests, don’t go looking for the six secrets of successful drawing – or anything else so determinate. Kentridge deals in the incompleteness, uncertainty and ambiguity of human life – but on a monumental, multi-media, multi-sensory and sometimes almost overwhelming scale. He does not seek to pin anything down and I wouldn’t attempt to do that with the work, either. This post is about some important things that I have taken from the experience of Kentridge’s work and which have inspirational and informative potential for the final part of my Drawing Skills studies.

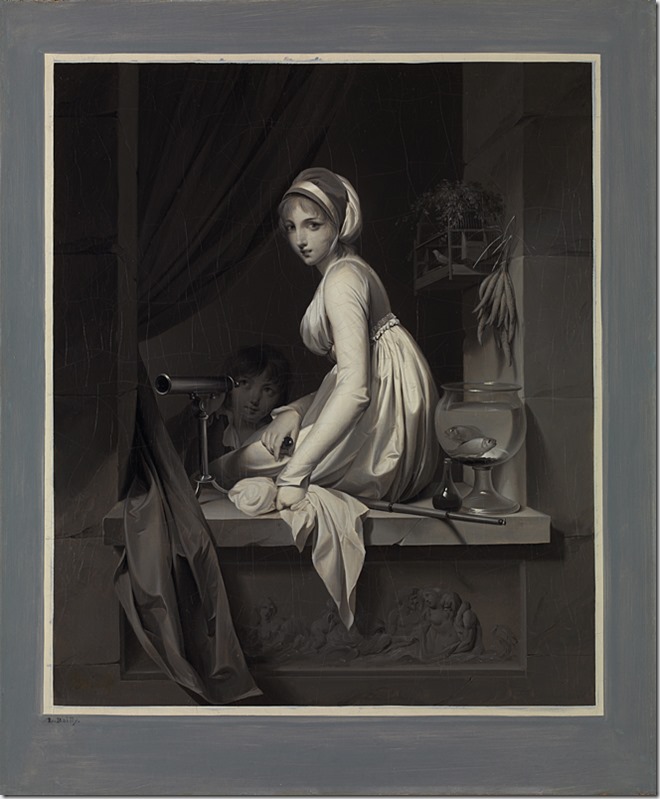

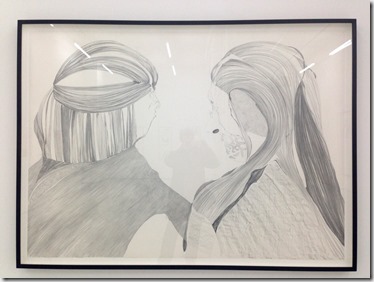

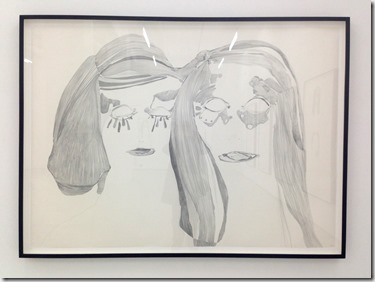

He draws. Drawing is at the heart of what he does – both literally, in the process of making the work, and ‘philosophically’ in the way that he thinks about the process (as in this excerpt from the Harvard Lectures – here). He draws in charcoal, sometimes ink, sometimes (as in the video clip) with shards and fragments that flow freely until combining into a recognisable form. And so there is inspiration in the notion that, essentially, an internationally acclaimed artist such as he, essentially, again, draws.

He is playful. The work is serious, intense, significant and deep; but there is something playful about Kentridge, behind the rather dour-looking, portly, sixty-plus figure that he presents (and through which he is ever-present in his work). The studio-based, filmic pieces in ‘7 Fragments for Georges Méliès’ demonstrate that aspect of his creative process, for example this. I might have begun this paragraph with ‘he entertains’, because I think he does. ‘The Refusal of Time’, for example, a 30 minute, five screen video projection that fills three walls of a room as well as presenting a huge, moving, wooden sculptural installation in the middle of the floor, is concerned with “… relativity, string theory and black holes, as well as the turbulent history of industry and colonisation” (Exhibition Guide) – a conceptual ambition matched by the overall scale, one might say. But it has a lightness to it, a sense of whimsical humour at times – not least in Kentridge’s own persistent presence. For me, ‘good art’ (![]() ) draws us in at what might seem, as ‘entertainment’ or whimsy, a superficial level; but once we’re there, we are rewarded and challenged by the potential of what we find (which leads into the next point).

) draws us in at what might seem, as ‘entertainment’ or whimsy, a superficial level; but once we’re there, we are rewarded and challenged by the potential of what we find (which leads into the next point).

His art is open-ended and non-directive. I’m repeating myself, to an extent – this is the point being made by Kentridge himself through the quotes in my opening paragraph. It’s not so much, for me, that the work poses questions; more that, like life, it presents a flow of experiences from which we make what we can. And we’ll never fully comprehend it all; nor should we expect to. It is art to be experienced.

He animates. This is more of a ‘formal’ response, but a potentially important one for me as I take my drawing forward. The basis of Kentridge’s work is, as I’ve said, ‘drawing’, but so much of the process and presentation is ‘animation’. What has been still appears to move and, through the movement, our experiences and our reading of the work also moves, to a new level. I suppose, and this takes me into a more complex theoretical area that I don’t intend to develop in this post, that the movement increases the likelihood that we are tempted to read narrative into what we are watching. I am looking at some theoretical writing on experimental animation, to which I’ll return later, and one of the characteristics identified is that it doesn’t, typically, feature “… causally linked events which occur in a defined time and space …” (Paul Taberham; ‘It’s alive if you are – defining experimental animation’, in Experimental Animation: from analogue to digital). So, Kentridge’s animation is not setting out to tell us a story, but the movement adds another formal, experiential level to the work – non-linear, non-directive, of course, but another aspect of the ‘drawing in’. The process aspect of his animation has also interested me. He describes it here. Interesting that his films develop without too much of a pre-conceived direction – no storyboard, he says. And the process of making the animation that is illustrated in the film has a kind of meditative aspect to it. It’s a slow, laborious, and in this case, non-digital process of building something as he goes along, thinking as he goes.

This latter idea is something that I have particularly latched onto from looking at Kentridge. I like the idea of adding a level of animation to my drawing; and I am interested, too, in the way this can add another creative process into this digital/physical interface, the space in which I am keen to ‘play’. I’ve begun with a small digital experiment: Animation experiment. It is an experiment, not a work of art ![]() !

!

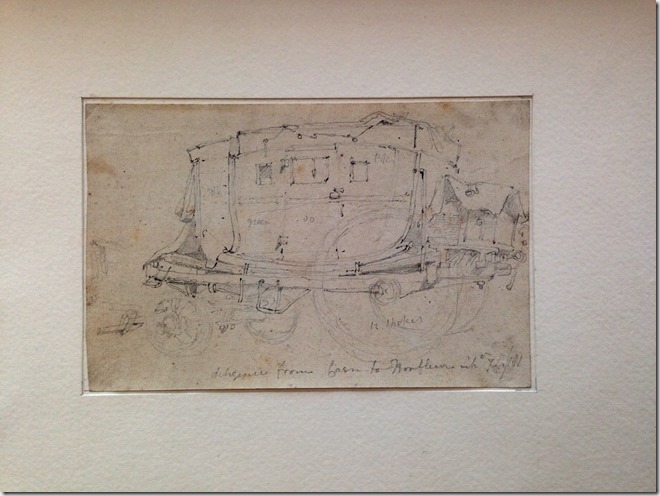

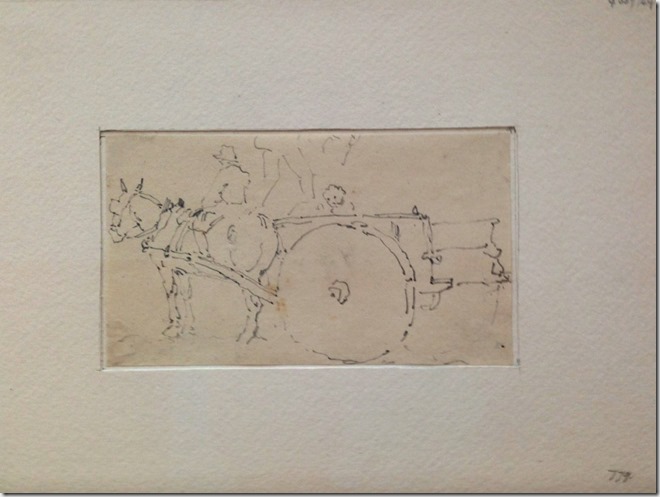

And then back to William Kentridge; as is clear from what I’ve written here, the Thick Time exhibition and my supportive reading and research have proved inspirational and informative of some potential ways forward with my work. Animation, in particular, has caught my imagination and I am going to explore its application to the project based on William Hoole’s old exercise book. In fact, and finally, here is another positive from the Kentridge work – he makes extensive use of books, usually old books, and particularly, in his case, as the ground for his drawing and subsequent animation. It has proved to be a very positive encounter.